Upskilling Tomorrow’s Independent Workforce

How workers stay learning, and companies retain learnings, in the new independent work economy.

In the last Dispatch, we explored a near future where many traditional full-time working relationships give way to short-term contract or “gig” arrangements. These will give both firms and workers more flexibility to define the work they do as they see fit. We think this era will be characterized by the “resurrection of the artisan, with knowledge workers acting as free agents, maintaining a commitment not to their employers, but to their craft.”

Sounds cool, but if the future knowledge worker is a nomadic craftsman with more loyalty to their craft than their employer, how can firms retain the talent they need for continuous, long-term transformation? And if the walls of the firm are porous enough to allow for a continuous shifting of responsibilities between contract workers, how can companies preserve the institutional knowledge that gives them value as firms?

To arrive at that answer, let’s first explore the other side of the equation, from the perspective of the worker. How can independent workers continue to learn and grow their skill sets if client firms don’t see them as long-term assets?

Leveling up, when the levels aren’t clear

Industrialization ended the era of the artisans, the master craftsmen who owned and mastered their tools of production and thus dictated the terms of their employment. “Upskilling” was baked into the artisanal model; expertise grew over time, and masters trained apprentices to follow in their steps. The factory upended this model, offering unskilled workers the opportunity to do one small, simple thing, over and over. Employees didn’t need to be extensively trained, and they were paid for their time rather than the quality of the work. On the lower end of the skill spectrum, workers toiled until they collapsed, at which point they could be easily replaced, because the work had been templatized to eliminate the need for skilled craftsmanship.

The predominance of the factory model across 20th century life was total. Factory-style organization was copied, its philosophies and practicalities bleeding into education, for example, with groups of roughly 28 students taught in similar classrooms staffed by a single teacher, around the U.S. and beyond. It also influenced how knowledge workers were organized. So-called “white collar” workers also worked a typical 9-5 workday, despite their distance from the machines that demanded a standardized schedule. The cubicle farm extended from the assembly line, an attempt to standardize knowledge work.

No longer in possession of the means of production like their artisanal forebearers, knowledge workers came to work for large firms, often spending their entire lives with a single company. They were rewarded for their loyalty to their bosses and their effort in climbing the corporate ladder within their organization.

Due to a number of factors that we’ve discussed over the last few Dispatches, we are now witnessing the resurgence of the artisan model, in the form of the independent knowledge worker. Wielding software tools that can be applied anywhere, the new skilled, independent generation of artisans represents a growing sector of the economy.

That’s a good thing, because the world needs more skilled workers. According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2020, companies estimate that, by 2024, around 40% of workers will require reskilling of up to six months, and 94% of business leaders say they expect employees to regularly pick up new skills on the job. The World Economic Forum also estimates that wide-scale investment in upskilling has the potential to boost GDP by $6.5 trillion by 2030.

When you work full time for a firm, career paths are often rather straightforward, with roles clearly reflecting where employees stand in the hierarchy (e.g. Manager, Sr. Manager, Director, Sr. Director, VP, CEO). Titles mean different things at different firms, but it’s not terribly difficult for an HR professional to figure out how much experience a prospective hire has by looking at their current and past titles.

Longtime independent workers on the other hand, are more difficult to evaluate, as they can make up any title they want, and can’t rely on a string of official title changes to reflect the progression of their career, or their growing professional value. It becomes incumbent upon the freelancer to take their continuing education into their own hands, both for the purposes of genuinely advancing one’s skills, and to broadcast professional growth to potential employers.

Some think that micro-certifications are the answer. Wiley’s Krysia Lazarewicz writes:

Stackable credentials — expandable qualifications, often parts of educational sequences — have become a critical pathway for learners to advance their careers, gain higher pay, and display competency in a shorter timeframe than full degree programs allow. These credentials — also known as micro-credentials, certificates, digital badges, and nanodegrees — are valuable signals for employers, especially since the COVID pandemic.

One such professional educational provider is Credly, a digital badging platform that issues and displays credentials. If LinkedIn is asking “Where have you worked?” Credly is asking “What have you learned?” Users can earn badges that are specific to a school, a professional organization, or even an individual product (think “Salesforce Certified Administrator”). It’s a way for employers to find, recognize and deploy talent within their ranks, or find external talent with competencies they need. Credly is an attempt to verify and quantify the value of a person’s skills, making it easier for HR to make quick hiring and contracting decisions, and on the other side, giving workers a means of broadcasting their skills.

We asked the Gather Network about their plans and preferences around upskilling. At a base level, 95% of respondents indicated that they spent some amount of time each year devoted to upskilling, aside from performing paid work. A little more than half of respondents are seeking some type of upskilling to continue to progress their careers.

Unsurprisingly, independent workers are self-directed in their professional education. 71% of respondents told us that clients never offer to pay for them to be trained. This may explain why 46% of respondents told us that they sometimes don’t feel like they’ve been sufficiently trained to be productive in a new project.

The most popular form of professional education among the Gather Network is independent reading, at 95%. 70% take short-term classes or courses, and 65% attend workshops and conference seminars.

Mentorship was the second least popular option. Is it possible to resurrect the master-apprentice dynamic that defined the artisanal era, so that knowledge can be disseminated across vast distributed networks of independents?

“Most of my career advancement, I owe to mentorship, even though it’s never officially labeled as such,” says Gather’s Director of Content, Jason Oberholtzer, who’s been independent for 12 years. “I try to pay that forward. When someone shows aptitude and interest, I show them more and more detail on how a thing is done, and ultimately hope to give them the reins to either run the project along with me, or run the next one. That’s how I learned most of what has helped me expand my skill set — from people who weren’t afraid to share their wisdom, and ultimately their responsibility.”

While many independent workers are shouldering the burden of their own education, we think it’s in the interests of large firms to offer educational opportunities — even when it comes to contractors.

Cultivating a Talent Ecosystem

Precariously employed Millennials and Zoomers have heard about how it used to be in the olden days: You got a job with a large firm and spent your entire career there, steadily climbing the ranks, with elder pros showing you the ropes, directly imparting the company culture, and your compensation package swelled proportionally to your rank in the clearly-established hierarchy.

Firms — according to legend — invested in their employees’ professional growth, because they knew if the employees were likely to stick around, they’d pay back that investment in higher-caliber output over the decades.

For many firms and workers, this vision of professional life and organizational harmony has been obliterated by sweeping economic and technological trends. We no longer expect firms to invest much in our professional development because we likely don’t plan to be around for long. We know it, and they know it. Today, 80% of CEOs rank the need to facilitate upskilling as their biggest business challenge.

Sometimes employers don’t need to retain talent, instead staffing up and down for short term projects as needed. But in many cases, organizations want to maintain good relationships with independent workers, as it cuts down on the transaction costs that gave rise to the gig work phenomenon in the first place. Furthermore, high turnover can result in the evaporation of institutional knowledge and company culture.

Top tech companies like Google, Amazon and Facebook recognize that to drive transformation, they need to attract engineers who are true craftsmen. These are people who love code and love to code. The problem firms face is that such engineers are in high demand and can work pretty much anywhere they want. Craftsmen engineers tend to not be particularly loyal to firms, but to the broader technology communities within which they operate.

To help attract top talent, large firms invest in what might be called “greater good” tech applications. For example, FAANG companies all invest heavily in machine learning by funding research projects, sponsoring events, hosting internal discipline-based meetups and mentorships, facilitating skills-based volunteer opportunities, and giving their employees ample opportunities to establish themselves within external technology communities. These investments may not translate into direct business value for the firms, but these companies maintain this level of participation because it communicates to the engineering community that they actually do care about the technology. And furthermore, that their engineers not only get to work with the latest tech, but on it. This community participation doesn’t come cheap, but it allows firms to attract, retain and upskill talented, enthusiastic engineers. These workers are given opportunities to grow within and beyond their roles, and they are more likely to stick around, or return after a hiatus. In the age of the artisan, worker loyalty and retention is worth far more than a steady rotation of cheaper talent.

According to David Gaspar, Partner and Head of Innovation at Gather, firms should think of their workers, both full-timers and contractors, sort of like how universities think of their alumni. When a student graduates from a prestigious school, her relationship with that school usually doesn’t terminate upon receipt of the diploma. The student is, in a sense, linked with that institution. For the rest of her career, she’ll be a graduate, and her attitude toward the school will contribute to that school’s brand value. Her successes will be the school’s achievements as well.

Gaspar suggests that a firm’s brand is more than simply how the brand is perceived in the mind of those who consume its products. It’s also about how its “graduates” are perceived. Firms need to develop strong brand identities as employers, so that people will want to work for them, and will be impressed when they hear that a new acquaintance spent some time with them, even if only for a year-long contract.

“You don’t have 40 years and a gold watch anymore,” says Gaspar. “Your company needs to be not just a great place to work, but a great place to be from.” Today, it goes both ways: just as workers must prove their value to their employers and clients, firms now also must prove their worth to current and future workers.

Investing in educational or upskilling opportunities for workers who may only be around for a short period may seem like wasted resources, but brands need to think about the long term.

“You are your people,” says Gaspar. “If the people who are working at your firm are fantastic because you’ve invested in their development, they’re still creating value for you in the market even after you’ve parted ways.”

When you hear that a new acquaintance attended a prestigious school, you might assume they are intelligent, accomplished, or ambitious. You may have a similar reaction when you find out that a person spent time at a leading tech firm or investment bank. This isn’t only because these are successful institutions. It’s also because they invest heavily in their people, and that includes ongoing career development, so people know that if you worked there, you’ve been cultivated by that institution at some level. HR folks should start asking themselves: Does our company evoke such a reaction when people hear about it?

“These people out there in the market are a reflection of you and your brand,” says Gaspar. “So you shouldn’t look at someone who just left after you spent three years upskilling them as a brain drain, you should see them as an ambassador of your brand, and their achievements are testaments in part to your value as an employer.”

Fast Company’s Ben Reuveni seems to agree with this sentiment.

“Modern careers are no longer ladders,” he says. “They are lattices of vertical and horizontal opportunities, shaped by personal and professional aspirations, in addition to company needs… Keep your employees engaged, no matter where they are. It’s incredibly competitive, and you really need to pony up and demonstrate that you’re invested in them.”

Preserving Institutional Knowledge

According to Gartner, professionals spend half their time searching for information, taking an average of 18 minutes at a time to locate a crucial document. While Gartner projects that AI and other technological solutions will proceed to bring this number down, we expect these gains to be undercut as personnel movement becomes more dynamic, with workers coming and going more frequently, at varying levels of commitment.

A company’s worth will increasingly be retained not in its people but in its processes, culture, and brand value. But people still have to create the processes, culture, and brand. While some of this knowledge is translated into written company policies and procedures, much of it lives inside their heads. When they leave, some of that institutional knowledge is lost. Even worse, new hires or contractors can come in with their own agendas, and fail to build on earlier knowledge, or take into account hard-earned lessons from the past. When an organization severs a relationship with an agency, or merges with a new company, institutional knowledge can easily fall through the cracks. How can organizations preserve critical information when talent is moving so freely in and out?

The first step is to identify the things that you want everyone in your organization to know — including independent workers — when they join your organization. What’s your company’s history, values, and brand identity? What is its position in the marketplace? What are its products? Where is your company trying to be in one, five, 10 years? Who are the customers, and what are their needs? Where can one find employee resource groups and how can they chart a successful growth plan?

These questions may seem basic, but it requires an intentional approach to put them together and make them so accessible that they can “come to life” within the organization. Once company-wide knowledge is written out, resources can be developed that speak to the specific fundamentals of divisions and even individual teams.

The second step is to build a repository for institutional knowledge. This repository can and should comprise multiple formats. Some companies eschew email entirely and save every internal conversation that happens via Slack, or similar messaging platform. Sifting through Slack channels has a low signal-to-noise ratio, but at least it’s all there, in the event of an emergency. With Slack, every bit of internal written communication is easily accessible and searchable forever, in one place. You can’t do that with email — at least not easily.

Some companies build expansive internal wikis, using platforms like Nuclino or Guru. Other knowledge base tools can be used for more specialized needs. These repositories can make different types of data accessible to the whole organization. For example, HR policies, software documentation, process guides, and employee photo bios. Management can use the wiki as a mouthpiece to the entire company, and line employees can quickly save important information that might be useful to their teams, as well as their eventual successors.

Technology solutions help, but human processes are also essential. Building a culture of information retention is a worthy goal. Processes must be proactive rather than reactive. For example, one way to reinforce such a culture is to conduct not just onboarding but “offboarding” sessions — and not only for full-time employees. You can also build knowledge retention practices into everyday workflows and develop incentives for participation. No worker is going to contribute to a knowledge base unless they are being compensated for their time. If participating in information retention is seen by workers as an unappreciated task for which there is little or no compensation, they’ll view it as unnecessary or unworthy of their time.

For Gather Managing Director Ben Edwards, institutional knowledge isn’t so much a “thing,” but a “process.” Organizations, he says, should think about maintaining the continuity of the process of knowledge development, so that information isn’t sitting inside one person’s head:

First we must determine the domains of knowledge that are core to our health and prosperity, as an organization. For each domain, we must ask, “What is the current process by which knowledge is created? Who are the parties to that process?” Maybe the knowledge creation process doesn’t always involve employees. Maybe it happens with partners or customers or suppliers. We need to know how these parties interact with each other, and then we can determine how we can improve these processes, and how we can make sure they accelerate so knowledge forms and accumulates faster.

With a strong understanding of how knowledge is generated, organizations can build successful knowledge retention strategies, and maintain continuity of work, even when high level workers are moving easily in and out of the organization’s four walls.

Fall Outlook

Gather Network survey respondents are optimistic as we head into Q4, which is to be expected given our distance from the fear, uncertainty, and doubt that characterized the first year of the pandemic. In the next Dispatch, we’ll have a full year of data to draw from, and we’ll be able to chart some longer trends.

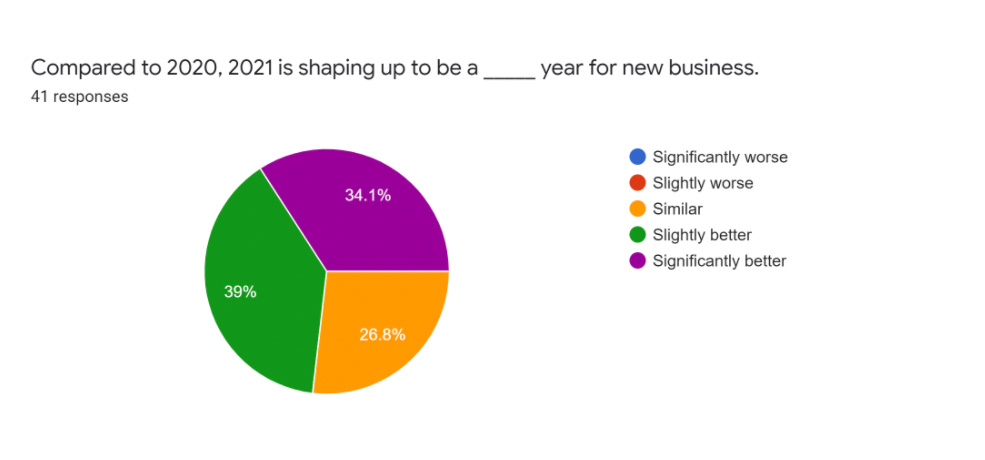

At the end of Q3, 34% of respondents think 2021 is going to close out as a “significantly better” year for business than 2020, and 40% believe it will be “slightly better.”

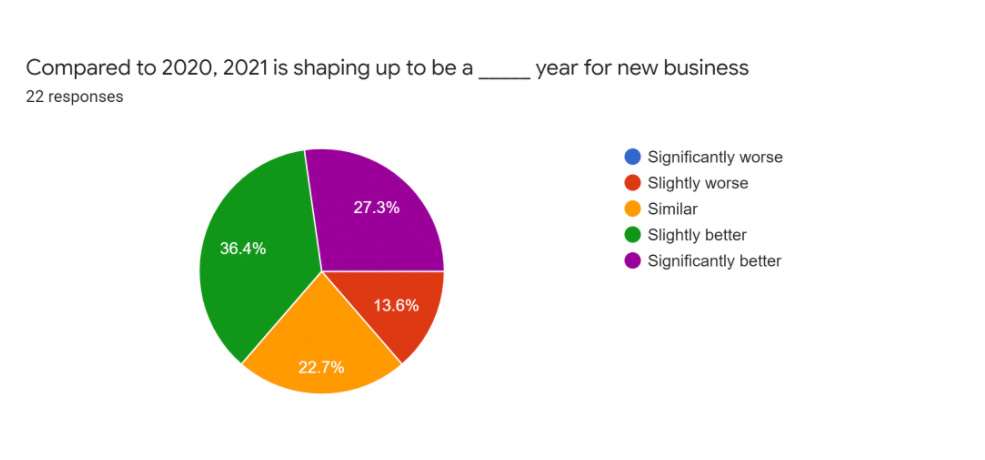

This is a significant improvement from our last survey we took six months ago:

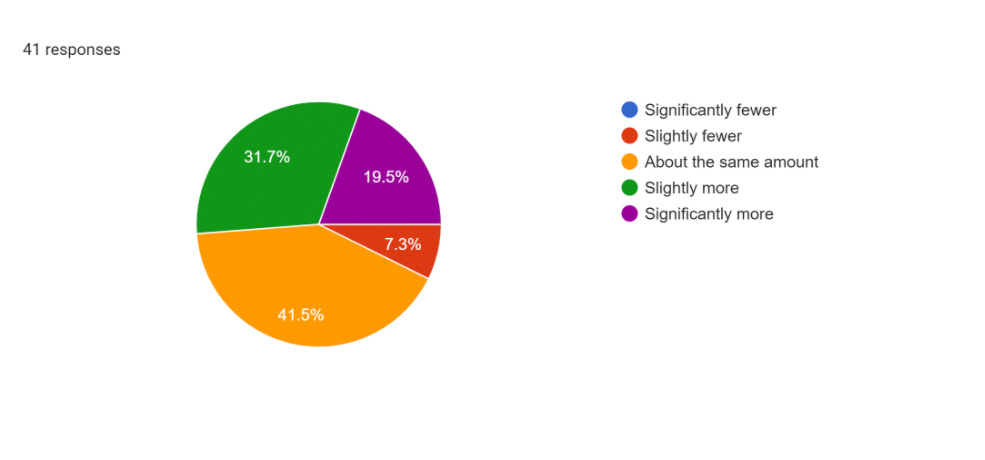

Respondents have been connected with more new work opportunities in the back half of the year as the front half:

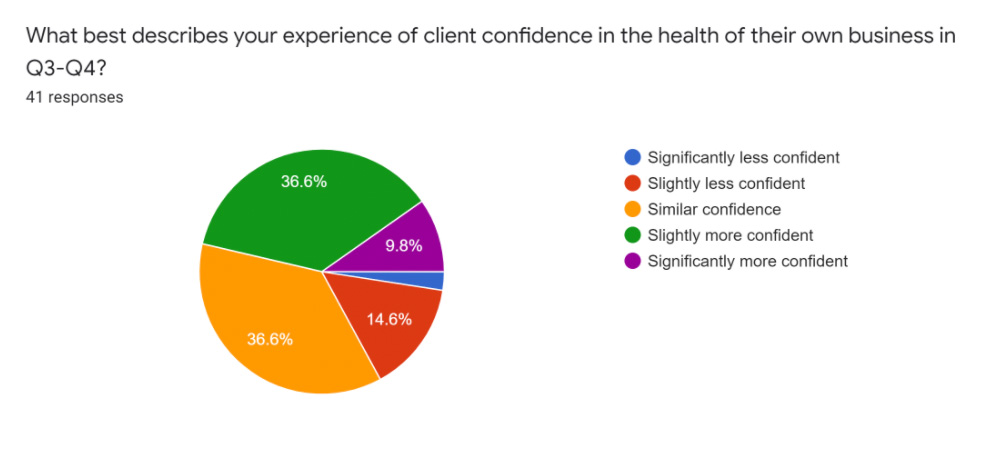

Client budgets and client confidence in the health of their businesses is on a slight rise, but it’s a big improvement from where expectations were at the close of Q2.